Migrations

|

Privateering and captivity in the Mediterranean

Overview

Before the age of mass migration, privateering, a central and legitimate component of international relations between the 16th and the early 19th centuries, was a major cause of the forced migration of thousands. From the Mediterranean to the USA, and even in northern European waters, governments granted private shipowners and entrepreneurs the right to attack and loot enemy ships, take a share of the profits from booty and take prisoners for ransom or sale. All the major conventions signed between European powers and rulers in the Near East and North Africa mention privateering as a political, military and economic reality and regulate its geographical scope. Ransoms, tributes and the tragedy of slavery became commonplace as a result of privateering, which was mainly undertaken from Malta and Livorno on the European side and Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli in North Africa. In 1815, following the Congress of Vienna, peace in Europe, the advent of steamships and the official abolition of slavery in the mid-19th century put an end to privateering.

More about

Privateering and captivity in the Mediterranean  Overview Overview Privateering in the Mediterranean Privateering in the Mediterranean Captives Captives Military slaves or Mamluks Military slaves or Mamluks Sub-Saharan African slaves Sub-Saharan African slaves |

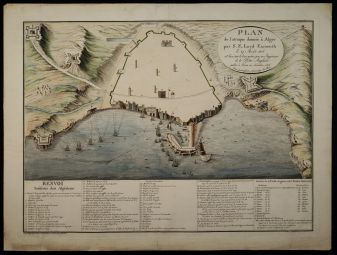

Chorographical plan of the attack waged by Lord Exmouth against Algiers on 27 August 1816

December 1816 State Archives of Turin, Turin, Italy Joseph Conti Control of the Mediterranean was a main source of conflict between the European powers and the North African provinces known as the “Barbary” Regencies, with headquarters in Tunis, Algiers and Tripoli. The term Barbary appeared in the 16th century to refer to North African (Berber) pirates, originating among the officers of the Sultan of Istanbul sent to conquer the western Mediterranean.  See Database entry for this item See Database entry for this item |

In this Exhibition About the Exhibition About the Exhibition

Privateering and captivity in the Mediterranean Privateering and captivity in the Mediterranean Migrations within the Ottoman Empire Migrations within the Ottoman Empire North–South movements North–South movements The life of European immigrant communities: Egypt and Tunisia The life of European immigrant communities: Egypt and Tunisia

|

/ Download

/ Download