Collections | Rediscovering the Past | The birth of archaeology | Biblical archaeology [7 Objects]

1872

The Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)

London, United Kingdom

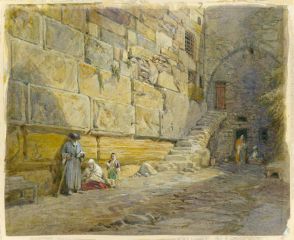

The Western Wall of the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, as depicted for the readers of the Illustrated London News by British pioneer war correspondent William “Crimea” Simpson. Simpson’s sketches were turned into engravings for publication in the ILN and, being among the most important graphic depictions, helped to introduce Western readers to the present-day appearance of Jerusalem and Jerusalemites.

Foundations of Haram al-Sharif

1872

The Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)

London, United Kingdom

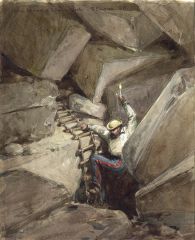

Foundations of the south-eastern corner of the Haram al-Sharif, as revealed for the first time by Charles Warren of the British Corps of the Royal Engineers. This tunnel was some 85 feet below ground. Warren’s team were experienced mining engineers, and were assisted, as shown in several of this sequence of watercolours by William “Crimea” Simpson, sent to record the expedition for the Illustrated London News, by extremely courageous local Jerusalemites.

1872

The Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)

London, United Kingdom

Foundations of the south-eastern corner of the Haram al-Sharif as revealed for the first time by Charles Warren. This tunnel was some 85 feet below ground. Warren’s team were experienced mining engineers, and were assisted, as shown in several of this sequence of watercolours by William “Crimea” Simpson, sent to record the expedition for the Illustrated London News, by extremely courageous local Jerusalemites.

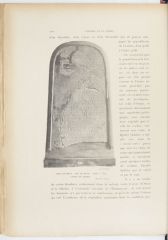

The Stele of Mesha, Hebrew inscription from 896 BC. 1/16 of original size

1873

National Library of France

France

The Mesha Stele gripped the European reading public. It touched on two areas of enormous interest: archaeology’s relation to the Bible, and ancient languages and writing (in this case, Moabite, an ancient Semitic language).

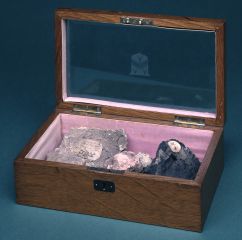

The Black Obelisk of Assyrian King Shalmaneser III

Obelisk: 825 BC; photo: 1876

The British Museum

London, United Kingdom

The Black Obelisk of the Assyrian King Shalmaneser III was excavated by a British expedition at Nimrud (Iraq) in 1846. There was great excitement when it was found to contain reference to biblical King Jehu. Furthermore, it depicted his image, still the oldest known image of a King of Israel.

The Stele of Mesha, King of Moab, c. 850 BC. Ruins of Dhiban

1905-1908

National Library of France

France

In 1868 a missionary named Augustus Klein found a stele at Dhiban (Jordan). It is inscribed with a long text describing conflict between King Mesha of Moab and the kingdom of Israel, including a parallel to an episode recorded in the Bible (2 Kings). The following year it was destroyed by the local Bedouin tribe, to prevent the Ottomans gifting it to Germany. The pieces were collected, and restored for display at the Louvre (Paris).

Close

Close

See Database Entry

See Database Entry