Collections | Migrations | Privateering and captivity in the Mediterranean [28 Objects, 3 Monuments]

17th–18th centuries

Place Halfaouine, Tunis medina, Tunisia

This mosque was built by Yusuf Sahib al-Taba’a, originally a captive of Moldavian descent. A favourite and then minister of Hammuda Pasha Bey of Tunis (1782–1814), he also served as Lord Chancellor and superintendent of taxes. In fact, he was the second most important political figure in the Tunis Regency after the bey himself.

18th–19th centuries

Tunis medina, Tunisia

Mamluk slaves often assumed great importance in the societies of their new homelands. The Dar Hassine was named after its builder, a Mamluk of Circassian descent. A close companion of General Khayr al-Din, the reformer of modern Tunisia, he also served as the first president of the municipality of Tunis (1858–65).

Algiers, 12 March 1787

State Archives of Naples

Naples, Italy

The Dey of Algiers thanked the King of Naples for the truce he granted to the privateers of Algiers.

1792

State Archives of Naples

Naples, Italy

Privateering wars were constant problems in the Mediterranean. Here, the frigate of the Kingdom of Naples is seen destroying the privateers from Algiers, the most important privateering hub in North Africa. The incident took place in 1792.

1797

Archives Nationales

Tunis, Tunisia

Throughout the 18th century, relations between the Regency of Tunis and the kingdoms of Italy and Tuscany were confrontational. There were also many Muslims captured in Spain and Malta. In 1798, after Malta was taken by Napoleon Bonaparte, all of the Muslims being held there – around 2,000 people – were released.

Treaty of Peace and Trade between France and the Tunisian Regency

1799

Archives Nationales

Tunis, Tunisia

Until the early 19th century, relationships between European powers were dominated by the consequences of privateering in the Mediterranean. The treaty signed guaranteed the safety of the crew and cargo of French ships at sea and in Tunisian ports.

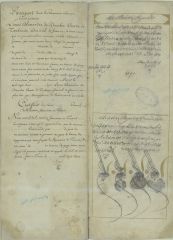

Passports that French ships were obliged to carry in order to be allowed to practice privateering

1799

Archives nationales

Tunis, Tunisia

A type of document bearing a seal and a signature that had to be carried by French ships to ward off attacks from Tunisian privateers in the Mediterranean.

List of the Christian captives of Italian origin, written by Mariano Stinca, a Neapolitan captive

1800

Archives Nationales

Tunis, Tunisia

Mariano Stinca was a captive of Neapolitan descent who ended up in the service of Hammuda Pasha, the Bey of Tunis (1782–1814). After a long period of activity as a statesman, head of protocol and interpreter, he left a large volume of correspondence written in Italian, now an invaluable historical source.

Disembarking captives at La Goulette Port, Tunis

1800

Archives Nationales

Tunis, Tunisia

This print shows privateers overseeing the unloading of captives at the port of La Goulette, Tunis. Some captives might regain their freedom after paying a ransom, but most were put to work or had to serve as galley slaves. Others who converted to their captors’ religion and where sufficiently qualified could become important state officials. Eligible women might end up in royal households and even as wives of princes.

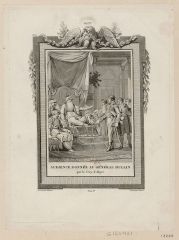

General Hullin's audience, provided by the Dey of Algeria

19th century

National Library of France

Paris, France

Algeria was the foremost privateering hub in North Africa, focusing primarily on the attack of British and French vessels. In August 1802, riled by the constant Algerian looting of French ships, Napoleon Bonaparte sent General Hullin with a warning message to the Dey of Algiers, Mustapha Pasha.

19th century

Le Bardo, Tunis, Tunisia

Many prisoners captured by privateers were sold to serve as labourers. The Bardo Palace in Tunis, the official residence of the ruling bey, is a sprawling complex of buildings constructed and fitted out in stages by architects and Christian captives throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

19th century

Palais de la Rose – Musée de l’Armée

La Manouba, Tunis, Tunisia

These flags represent the late 18th/early 19th-century emblems of a privateer acting on behalf of the Regency of Tunis. Unlike pirates, privateers were commissioned by governments, and their maritime activity was referred to as privateering. They were given authorisation to attack enemy merchant ships during war time.

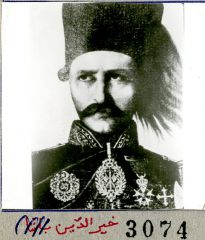

19th century

Institut Supérieur d’Histoire Contemporaine de la Tunisie

La Manouba, Tunis, Tunisia

Khayr al-Din Pasha was a Mamluk of Circassian descent, raised at the court of Ahmad Pasha Bey (1837–55). He later assumed the powerful role of Great Vizier of the Regency of Tunis (1873–77), initiating many crucial policies aimed at reforming the state structure, education and the national economy.

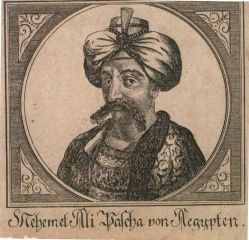

Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1769–1849)

1st half of the 19th century

Austrian National Library

Vienna, Austria

The end of the Mamluk system came about in the mid-19th century, partly due to the abolition of slavery. In Egypt, the local Mamluk power structure and its last representatives were eradicated by Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1805–48) with the objective of consolidating his absolute power over the country.

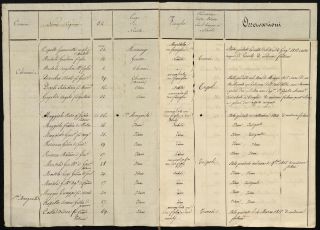

1808–11

State Archives of Palermo

Palermo, Italy

This document from the early 19th century lists “Tunisian Turks” who had been taken prisoner by a Sicilian privateer and taken to Palermo for sale.

5 August 1811

State Archives of Palermo

Palermo, Italy

Booty, including captives, taken during privateering raids was carefully assessed and administrated. This document lists “25 Turks from the Barbary coast”, who had been taken to Palermo for sale by Sicilian privateers.

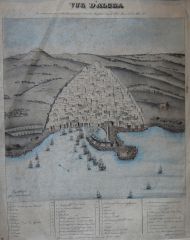

1816

Musée National des Beaux-Arts

Algiers, Algeria

North African rulers engaged in privateering not only because it was lucrative, but because their trading vessels were not allowed into European ports. Algiers – seen here before the bombardment by the British fleet in 1816 – was the foremost privateering city state until Algeria was conquered by France in 1830.

23 March 1816

State Archives of Genoa

Genoa, Italy

This list of enslaved men, women and children from Chiavari in Italy gives a a glimpse of the careful record-keeping after privateering campaigns. Many Italians were taken to Tunisia, many rising to serve as political or military officials. During the reign of Hammuda Pasha Bey, Italian even became the official language of correspondence with foreigners.

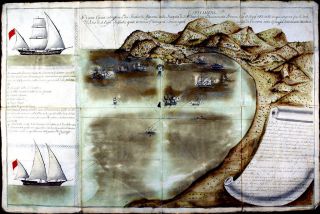

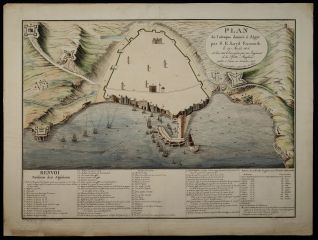

Chorographical plan of the attack waged by Lord Exmouth against Algiers on 27 August 1816

December 1816

State Archives of Turin

Turin, Italy

Control of Mediterranean trade routes was one of the main sources of conflict between European powers and the North African provinces, referred to as the “Barbary Regencies” of Tunis, Algiers and Tripoli.

Palace of Bardo (Tunis), 17 April 1816

State Archives of Turin

Turin, Italy

Following European warnings, in particular the expedition led by Lord Exmouth (1816) to prohibit privateering, a peace treaty was signed between the Bey of Tunis and Lord Exmouth, commander-in-chief of the Royal British Navy on 17 April 1816.

Close

Close

See Database Entry

See Database Entry